If you like to purchase a print or giclée please go to SHOP. For prices, and other specifics about the original artwork please e-mail artist directly arturogarciafineart@gmail.com

“Tatanka: The Spirit of the Land” Art Collection/Exhibit

If you like to purchase any of the images go to “shop“–if you have any other questions e-mail the artist at: arturogarciafineart@gmail.com

TATANKA: The Spirit of the Land

Scientists and anthropologists estimate 30-60 million bison roamed the North American Plains when the first European settlers came to this continent. They roamed by the thousands across three countries; from southern Canada to Mexico and from one ocean to another in the North American continent. This beautiful and majestic animal had everything the Native Peoples needed to survive the fierce winters in the Appalachians and the hot summers in the endless plains and the Mojave Desert region. Both bison and men coexisted for hundreds of years. They shared the land in all corners of North America. They knew each other intimately and depended on each other for survival.

Entire Indian Nations and Cultures flourished with Tatanka at the core of their lives, mainly as means of sustenance. The buffalo, as they called the largest land mammal of the Americas, was the central part for many Indian cultures. Their presence meant spiritual strength, but more than anything, it meant survival. Food, clothing, tools, utensils, housing, and even fuel are just a few of the many things the Native tribes obtained and benefited from the buffalo.

With the arrival of European settlers, a drastic change began to take place. The introduction of guns and horses changed the game for both Indians and buffalo as they could hunt them in larger quantities. As more people populated the Northern part of the newfound American Continent—land expansion, the birth of a new nation and the gradual submission of the Indians—the fate of the bison darkened, and with that, came the complete subjugation of the Indians. In the slaughter of the buffalo, the Indians saw their own fate.

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the Indian wars were coming to an end after the Battle of Little Big Horn in 1876 in Montana, Nez Percé in 1877, and culminating with the Wounded Knee Massacre in South Dakota in 1890. By then, the bison were almost extinct. During this last part of the century for the Indians and the buffalo, the Federal Government promoted bison hunting for various reasons: To allow ranchers to range their cattle without competition from other bovines, to clear way for the railroads, and most important, to weaken the Indians. Military commanders were ordering their troops to kill bison — not for food, but to deny Native Americans their own source of food. One general believed that bison hunters “did more to defeat the Indian nations in a few years than soldiers did in 50 years”. By 1880, the slaughter was almost over. Where millions of bison once roamed, only a few thousand animals remained. It is estimated that by the turn of the twentieth Century, only a few hundred bison survived the evil of men.

At present, the collaborative efforts of some of the remaining Indian Nations with organizations like the National Wildlife Federation, are working hand-in-hand to reintroduce bison to tribal lands. In November of 2016, after over 130 years, a small herd of 10 adult bison was reintroduced to the wild at the Wind River Reservation in Fort Washakie, WY where the herd bison was liberated to roam freely in tribal lands shared between the Eastern Shoshone and the Northern Arapahoe tribes. This event, called Boy-zshan Bi-den, or Buffalo Return in the Shoshone language not only has had a huge impact on the ecosystem but it also has brought peace to the two tribes who have been historic enemies.

Other groups like the American Bison Society, headed by zoologist William Hornaday and former president Theodore Roosevelt, have been key in rescuing bison from its impending extinction. Today’s bison population is higher than 500,000 and steadily growing.

Arturo Garcia.-

——————

Bibliography:

American Buffalo Spirit of a Nation (WNET.ORG, NWF, Devillier Donegan Enterprises), The Great Indian Wars (Mill Creek Entertainment), AMERICAN BISON—The Return of the Buffalo (WYCC PBS Chicago), Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation by Jonathan Lear, The Great American Bison by Jed Portman (Rocky Mountain PBS)

——————

“I can think back and tell you much more of war and horse-stealing. But when the buffalo went away the hearts of my people felt to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened. There was little singing anywhere.”

Plenty Coups, Chief of the Crows

Ta·tan·ka–tatənka is a Lakota word that literally means “Bull Buffalo.”

——————

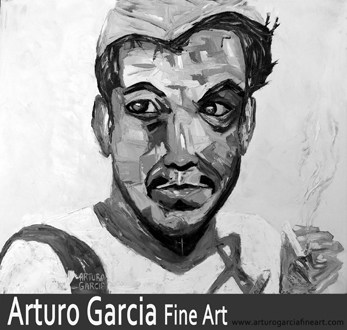

Artist Statement:

Tatanka is a collection of my bison paintings. With it, I intend to deliver a story about the largest and most iconic mammal in North America and the importance it had in the Native American Cultures from time immemorial. It is a hymn to stoicism; a eulogy to a great teacher (as seen with the eyes of a neutral spirit) and a way to observe the impact humans have in our own shared environment with other species.

As a migrant, like bison were once, this is my own personal tribute to the American Buffalo, to its long struggle to survival. This bison world I re-created with palette knives and oil paints aims to capture not only the life, but also the essence and the spirit of this beautiful animal we have adopted as our American symbol alongside the bald eagle.

With this exhibit I officially join forces with all the nature conservation entities to deliver an educative art presentation about the importance of bison, both culturally and nature wise. Praise to the largest mammal of North America, our new ambassador and to its conservancy!

Arturo Garcia.-